- Preface

- Chapter 1. State of the U. S. Foster Care System

- Chapter 2. Defining, Assessing, and Promoting Adolescent Well-Being for Youth in Out-of-Home Care

- Chapter 3. Technology Innovations in Foster Care

- Chapter 4. What’s Working in Mental Health Care? Leveraging Opportunities to Develop More Effective Services for Children in Foster Care

- Chapter 5. Development of an Integrated Medical and Behavioral Health Care Model for Children in Foster Care

- Chapter 6. Keeping Foster Parents Supported and Trained: Empowering Foster and Kinship Parents as Agents of Change for Children and Youth in Foster Care

- Chapter 7. What’s Working for Academic Outcomes for Youth in Foster Care

Chapter 5. Development of an Integrated Medical and Behavioral Health Care Model for Children in Foster Care

Kimberly E. Stone, MD, MPH University of Texas Southwestern Medical School, Dallas, Texas and Children’s Health, Dallas, Texas (OrcID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3551-4725)

Sara Pollard, Ph.D, ABPP University of Texas Southwestern Medical School, Dallas, Texas and Children’s Health, Dallas, Texas (OrcID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5799-3160)

Sara Moore, DNP, APRN, PNP-BC University of Texas at Arlington, College of Nursing and Health Innovation, Arlington, Texas and Children’s Health, Dallas, Texas (OrcID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6560-6298)

Abstract

Children in foster care are classified as a population with special health care needs. They face multiple adverse childhood experiences and disrupted relationships, yet face barriers accessing consistent, high-quality health care. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends integrated physical and behavioral health care for children in foster care, but little is known about the implementation of integrated care for this population. As a pediatrician, doctor of nursing practice, and psychologist in an academic medical setting, we describe the development and implementation of the Rees-Jones Center for Foster Care Excellence, emphasizing the role of medical and behavioral health providers in promoting the overall well being of children in foster care. We discuss the evolution of the integrated care model, as well as current initiatives for quality improvement, research, and advocacy; and future goals for evaluation, education, policy, and collaboration to improve the lives of children in foster care.

Keywords: foster care, integrated care, cross-system collaboration, behavior and physical health care, advocacy, out of home care, child welfare system

Development of an Integrated Care Health Care Model for Children in Foster Care: The Rees-Jones Center for Foster Care Excellence

Children in foster care are classified as a vulnerable population with special health care needs by the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), and many have unmet health care needs both before and after being placed in care (Szilagyi et al., 2015). Children in foster care have a higher prevalence of asthma and obesity (Turney & Wildemann, 2016). They are more likely to have delayed immunizations (Hansen et al., 2004) and higher rates of hospitalization with complex chronic problems than those not in care (Bennett et al. 2020). In addition to high rates of toxic and posttraumatic stress (Forkey & Szilagyi, 2014), children in foster care have high rates of psychotropic medication use and are more likely to be referred for mental health or developmental concerns than children not in care (Hansen et al., 2004; Turney & Wildemann, 2016; Dosreis et al., 2011; Raghavan & McMillen, 2008). Unmet health needs and multiple adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) increase the risk of ongoing health problems and poor health outcomes in adulthood (Bramlett & Radal, 2014; Felitti et al., 1998; Merrick et al., 2019; Zlotnik et al., 2012; Strathearn et al., 2020). Failure to address these issues can impact relationships, placement stability, and educational success (Rubin et al., 2007).

Most children in foster care are eligible for Medicaid health insurance because their care is supported by title IV-E of the Social Security Act (Child Welfare Information Gateway, 2015). Medicaid benefits vary by state, but all contain Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic and Treatment (EPSDT) services (Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services [CMS], 2014). Each state is responsible for implementing these federally mandated services, which include services for preventive medical care, dental health, hearing and vision screening, and behavioral health care (CMS, 2014). Many states have managed Medicaid plans specifically for children in foster care and have developed provider incentive programs and mechanisms for sharing health information (Pires, Stroul, & Hendricks, 2013). While these efforts can improve health care delivery, concerns of quality of care and access remain (Deutsch & Fortin, 2015, Pires, Stroul, & Hendricks, 2013). However, children in foster care often face barriers to accessing health care; up to 30% of children in foster care missed at least one recommended health screening (Levinson, 2015). Barriers include lack of access to their medical providers (PCPs) due to removal from their neighborhood and community, frequent placement changes, insurance coverage for providers and services, communication between child welfare and health providers, and a lack of health care provider training regarding the unique needs of children in foster care (Greiner & Beal, 2018; Deutsch & Fortin, 2015; Szilagyi et al., 2015, Raghavan et al., 2010).

For the child in foster care to thrive, a trauma-informed, integrated multidisciplinary approach to their care is needed. Educators, PCPs and behavioral health providers (BHPs), child welfare agencies, and caregivers should coordinate efforts and communicate regarding each child’s unique trauma history and needs. PCPs and BHPs can provide crucial health information to child welfare agencies, but communication between these professions is often lacking. Difficulties making phone or email contact, child and family privacy issues, and a lack of understanding regarding the players and organization of each system and their roles and responsibilities in evaluating child maltreatment are all recognized barriers to communication (Campbell et al., 2020). This can result in children not receiving needed medications, allergies, or missed appointments for chronic conditions. Children in foster care often have significant mental health and developmental needs, thus BHPs are often needed to address child behaviors and support and educate caregivers. However, barriers to effective collaboration also exist between BHPs and PCPs, including disparate training and focus, lack of training in a primary care setting, communication barriers, and differences in privacy policies (Kolko & Perrin, 2014; Levy et al., 2017; Mufson et al., 2018). Children in foster care have many health care concerns that can be best managed with both PCPs and BHPs, such as maladaptive eating patterns, sleep disturbances, abdominal pain and headaches, anxiety and depression, and elimination disorders such as enuresis and encopresis (Peek, 2013). Evaluations by PCPs and BHPs provide opportunities to assess educational issues, provide support and information to caregivers, and refer for learning and school difficulties (Berger et al., 2015; Whitgob & Loe, 2018).

Interest in improving and coordinating the care of children in foster care has increased over the past 20 years. The Child Welfare League of America (CWLA) and the AAP published recommendations for the health care of children in foster care (AAP, 2005; CWLA, 2007). These guidelines stressed the importance of medical and behavioral health evaluations within a few days of removal and in one month after a child enters foster care. Medical and behavioral follow-up is recommended at least every 3 months for the first year children are in care, which is more frequent than the standard annual health supervision recommendation for older children and adolescents (Hagan, Shaw & Duncan, 2017). The state government is obligated to ensure the health and safety of children in foster care, and the Family First Prevention Services Act underscores the federal government’s focus on child well-being by committing federal funds to prevention services. Including the child’s medical and behavioral health needs in both the family’s and the child’s reunification service plans is crucial (CWLA, 2007).

In 2015, the AAP reaffirmed the need for ongoing, coordinated health care for children in foster care (AAP, 2015; Szilagyi et al., 2015), stressing integration of medical and behavioral health services, and sensitivity to trauma. Despite these recommendations, the majority of children in foster care do not receive coordinated care that involves communication between child welfare, PCPs and BHPs (Deutsch & Fortin, 2015; Levinson, 2015; MeKonnen, Noonan, & Rubin, 2009; Terrell, Skinner, & Narayan, 2018). The remainder of this chapter will describe health care delivery models that can improve the care of children in foster care and detail the development of a trauma-informed, integrated medical and behavioral health care delivery model at the Rees-Jones Center for Foster Care Excellence at Children’s Health in Dallas, Texas. Benefits and challenges of integrated care and strategies for addressing barriers will be discussed.

Health Care Delivery Models for Children in Foster Care

Several models of care delivery, including those listed below, have been developed to address the medical and behavior health needs of children in foster care (AAP, 2020; Greiner & Beal, 2018; Johnson et al., 2013):

- Evaluation and referral: When a child enters foster initial entry to foster care or following a placement change, is referred to a dedicated foster care assessment center for a detailed evaluation, which could include medical, dental, and developmental-behavioral services. These centers may coordinate with child abuse evaluation clinics or be freestanding. After the initial assessment, the child is referred to a PCP in the community for ongoing care.

- Dedicated primary care: PCPs provide initial assessment and ongoing medical care in the same clinic, including health supervision, sick visits, and chronic disease management.

- Nurse coordination: These clinics are often based at child welfare office and provide case management and referral services.

- Behavioral care model: In this model, a behavioral health provider coordinates care, focusing on developmental-behavioral concerns and foster parent training to prevent placement breakdowns.

The Medical Home Model

The AAP described a medical home model for children as one in which children receive care that is “accessible, continuous, comprehensive, family-centered, coordinated and compassionate” (Dickens, Green, Kohrt, & Pearson, 1992). Care should include health supervision, acute and chronic illness treatment, and access to subspecialty care and community resources (Dickens et al., 1992; Sia et al., 2004). The medical home model is considered the gold standard of pediatric medical care.

There are many barriers to implementing this type of care for children in foster care. One tenet of a medical home is ongoing care with one provider. The PCP, who provides ongoing comprehensive general pediatric care, is the core of the medical home. Children in foster care may lack this continuity in PCPs when placed outside their community, experiencing multiple changes in placements, or experiencing repeated transitions into and out of foster care. Child welfare agencies, health care providers, and caregivers may not know where children have previously received care, which prevents continuity of care with previous providers and limits access to medical records (Szilagyi et al., 2015, Espeleta et al., 2020).

Integrated Care Models

Multidisciplinary collaboration among providers can improve health outcomes for pediatric conditions such as depression and Attention Deficit Disorder (ADHD) (Butler et al., 2008; Deutsch & Fortin, 2015; Zlotnik et al., 2015). Behavioral health issues are commonly identified by primary care providers, but lack of community resources or access to mental health providers can limit effective treatment (Godoy et al., 2017; Ader et al., 2015). Integrating BHPs in a primary care setting can benefit children in foster care, since PCPs often lack training in managing complex behavioral problems (Horwitz, et al., 2015). The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) defines this type of integrated care as “the care a patient experiences as a result of a team of primary care and behavioral health clinicians, working together with patients and families, using a systematic and cost-effective approach to provide patient-centered care for a defined population.” (Korsen et al. 2013).

Integrated care, at its core, is the coordination of medical and behavioral health care. There are five levels of care integration (Table 1) (National Council for Behavioral Health [NCBH], 2020; SAMSHA, 2021). The degree of integration ranges from referral and consultation, with rare communication, to a completely team-based system where PCPs and BHPs share visits, documentation, and patient management (NCBH, 2020; Platt et al., 2018). Implementation of integrated care at the highest level requires PCPs and BHPs to fully understand each other’s training, culture, and ethical standards. Providers must merge their respective cultures, with the ultimate focus on improving quality of care. This requires provider training and ongoing communication. Clinic space and processes must be designed to support collaboration, and information systems need to support co-management, patient support, and access to community resources (Kolko & Perrin, 2014). Barriers to implementing fully integrated medical and behavioral health care for children in foster care include lack of buy-in by clinic leadership, sustainability due to lack of reimbursement for shared visits, and the increased visit times.

Trauma-Informed Care

Medical and behavioral health care for children in foster care should be sensitive to the impact of their past traumatic experiences (Bartlett et al., 2016). Trauma is defined as the emotional, psychological, and physiologic response to distressing events, such as natural disasters, abuse and neglect, or medical trauma (Marsac et al., 2016). A trauma-informed practice recognizes the varied impacts traumatic experiences can have on health, behavior, and interaction with the health care system. This includes identifying those at risk for trauma, recognizing past trauma, and preventing additional trauma or re-traumatization during care (Marsac et al., 2016, Duffee, Szilagyi, Forkey, & Kelly, 2021, Forkey et al., 2021).

To truly practice trauma-informed care requires an understanding of the widespread impact of trauma, including how the trauma histories of providers, staff, and caregivers can impact a child’s care (National Child Traumatic Stress Network [NCTSN], 2018). This includes individual, institutional, historical, and cultural trauma experiences. Secondary trauma can also affect the family, staff, and system dynamics. Implementing a trauma-informed integrated approach to care is guided by principles of cultural humility, mutual trust and collaboration, and safety and requires collaboration across multiple sectors, leadership engagement, and monitoring (Bartlett et al., 2016; SAMHSA, 2014). Barriers to implementing trauma-informed care for children in foster care include lack of financial commitment by institutions, lack of provider and staff training, and time constraints of clinic visits (Center of Excellence for Integrated Health Solutions, 2017).

Trauma-Informed Integrated Medical and Behavioral Health Care

Children’s Health in Dallas had a long-established child abuse evaluation team with a smaller foster care support team. There was shared clinic space for serving a small number of children in foster care but no physical space for expansion. The formation of a statewide Medicaid Managed Care Organization specifically for children in foster care in 2008 streamlined referrals and standardized access for specialty care and other services throughout Texas. Speech, occupational, and physical therapy evaluation did not have to undergo prior authorization, and , behavioral health services and dental services were included. Statewide child welfare redesign focusing on caring for children close to their communities of removal provided opportunities for community collaboration. In 2009, in response to these changes, Children’s Health established an independent clinic for children in foster care to address system-level issues such as transitions in and out of care, fragmented health care, and lack of communication between child welfare and health care providers. In 2011, with support from the medical and child welfare community, an innovative care model with co-located general pediatricians and pediatric nurse practitioners, behavioral health specialists, and child welfare agency workers was piloted with a grant from the Rees-Jones Foundation. In 2014, sustained funding from the Rees-Jones Foundation and the Meadows Foundation allowed planning for the Rees-Jones Center for Foster Care Excellence to begin.

The goals of the center were to improve outcomes for children in foster care by addressing the barriers to accessing quality health care (see Figure 1). The center has three pillars: 1) excellence in evidence-based clinical care; 2) scholarly research and education of future health professionals; and 3) community engagement and advocacy.

Figure 1

Logic Model Addressing Barriers to Improve Health Outcomes of Children in Foster Care

Clinic Design

Physical Space.

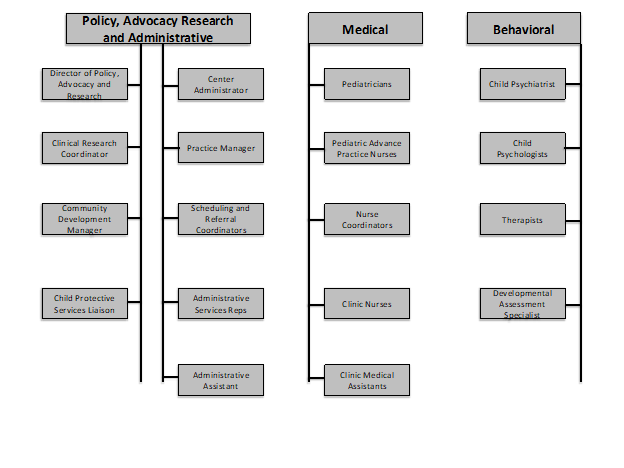

Initial planning focused on the development of physical space that allowed for multiple providers to be present during the visit. The waiting room has colorful artwork and twinkle lights on the ceiling, and most of the visit is conducted in an inviting interview room and playroom connected by a window, so caregivers can discuss sensitive issues but children can still be seen. The exam room is separate, and time spent in that “medical” environment is minimized whenever possible. Conference room and team room space allowed collaboration between medical providers, early childhood specialists, therapists, psychologists, learners, child welfare agencies, and clinic staff. Wellness spaces with soft lighting, comfortable seating, and no technology provide places for staff to debrief, breathe, and recharge. Both clinic sites were completed in 2016 and fully staffed in 2018 (see Figure 2).

Figure 2

Rees-Jones Center for Foster Care Excellence Organizational Chart: Clinical and Non-Clinical Staff

Integrated Clinical Care.

Following the recommendations of the AAP (Szalagyi et al., 2015), the Rees-Jones Clinic implemented an on-site, collaborative integrated primary care clinic incorporating elements of integrated care and patient-centered medical home and trauma-informed care models (Lamminen, McLeigh, & Roman, 2020; Pediatric Integrated Care Collaborative, [PICC], 2009) (Table 2). This model differs from “usual” medical care in a variety of ways.

Table 3 details a typical patient’s possible outcome when receiving care in the Rees-Jones Center compared to “usual care.”

(Bold font indicates Child Protective Services required visit, italicized indicates additional encounter at Rees-Jones Center)

Families are referred to the center by word of mouth from other foster families or from child welfare agencies; caregivers choose the center as the child’s primary care provider. In the initial visit, PCPs and BHPs assess the child and foster family together in a shared interview whenever possible. Extended appointment times (30-90 minutes) allow more time to address caregiver concerns. If there are urgent mental health care needs, the BHP can assess, safety plan, and arrange follow up as needed. All new patients are discussed in a weekly huddle that includes a psychiatrist, psychologists, licensed therapists, child development specialists, primary care providers, nurse coordinators, nurses, a child protective services liaison, and front desk staff. Nurse care coordinators ensure follow up on referrals and provide case management for medically complex patients. Collaboration with child welfare agency staff allows early communication regarding placement changes and court proceedings, which facilitates healthier transitions to the next placement or reunification and reduces gaps in care. When the Center is notified of a placement change, the clinic offers the new caregiver a transition phone call or visit. Nurse coordinators send a letter to the caseworker, new caregiver, and new PCP detailing medical and behavioral health concerns, current treatment, and recommendations for care.

Primary care services are team-based and comprehensive, including well-child care, sick visits, and care coordination to facilitate management of chronic medical issues as informed by the medical home model. A trauma-informed approach involves a shared interview to minimize re-telling of traumatic events, and discussions regarding removal or behavioral issues are conducted with the caregiver separately. Validated screeners for development (Ages and Stages), behavioral issues (Pediatric Symptom Checklist), and depression (PHQ-9) are conducted at all health supervision and follow-up visits. Behavioral health services include Trauma-Focused Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (Cohen, Mannarino, & Deblinger, (2012)) and Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (McNeil & Hembree-Kigin, (2010)).

After the initial visit, a child is referred to psychiatry for evaluation if needed. The level of integration of medical and behavioral services is tailored according to the needs of the child.

Collaborative Integrated Care Benefits.

A trauma-informed, integrated care model benefits children, families, and providers. A shared visit allows the child’s story to be told only once, limiting potential re-traumatization and redundancy. Early involvement of behavioral health allows timely identification of issues and prompt referral to services, which can decrease placement breakdown. Both PCPs and BHPs have expertise in foster care policy and are knowledgeable about community resources to help caregivers in accessing supports. Recommendations are made in the context of understanding trauma, medical concerns, and evidence-based treatments. Joint treatment planning allows the communication of a unified message, emphasizing both the child’s physical and mental health care needs, which can improve treatment engagement and reduce unnecessary intervention as well as confusion and stress for caregivers. For example, shared management of encopresis addresses the medical treatment of constipation and the behavioral consequences of sexual abuse and PTSD simultaneously. Opportunities abound for interdisciplinary consultation and training.

Collaborative Integrated Care Challenges.

Challenges with integrated care occur at the patient, provider, and system levels. Families did not always appreciate the benefit of seeing a BHP in the primary care visit. Some caregivers preferred shorter, less frequent appointments, especially when multiple siblings needed same-day visits. PCPs and BHPs who historically conducted visits independently now needed to share exam room space, time, and documentation. Processes for determining frequency and scheduling created administrative stress. The shared visits raised ethical issues for children with outside therapists. Electronic medical records were not equipped to schedule provider visits concurrently, and there was no process for billing. Legislation (Texas HB1549) mandating medical evaluation within 3 days of placement improved prompt access to medical care, but resulted in decreased availability of BHPs for the initial visit.

Clinic Outcomes

Reach of Services.

Over time, the Rees-Jones Center for Foster Care Excellence has served increased patient volume. In 2010, the foster care clinic saw 723 patients at one site and in 2019, the Center served over 2,000 patients at two sites, almost 20% of the children in foster care in the region.

Health Outcomes.

Measuring outcomes for children in foster care was part of the initial plan for the Center, but the first 5 years were focused on building and staffing the center. Hiring a Director of Policy, Advocacy and Research enabled increased focus on policy and the development of a research agenda and program evaluation plan. Strategies for obtaining data from electronic medical records required structural changes in documentation to allow accurate data retrieval and ongoing collaboration with data intelligence. Privacy concerns and issues surrounding center access of Medicaid billing data, consent for research studies, and use of data not obtained in the clinic are barriers to measuring health outcomes of children in Texas foster care. Current projects include descriptions of our clinic population, caregiver stress, resilience, and implementation of recommended laboratory screenings, and evaluation of the impact of evidence-based psychotherapies.

Community Involvement, Advocacy, and Policy

The Rees-Jones Center is committed to developing relationships with community stakeholders involved with the care of children in foster care. When a child with complex medical or behavioral health care needs is not getting access to needed services or is at risk of placement breakdown, or a return to the biological parents is planned, center providers or child welfare staff can schedule a collaborative care conference. These conferences include the clinic treatment team (PCPs, BHPs, nurse coordinator), child welfare personnel, community supports (behavioral supports, speech or physical therapists), and foster or biological parents. Care conferences allow everyone involved in the child’s care to identify and propose solutions to benefit the individual child.

Working with child advocacy agencies at the state level resulted in the passage of legislation (Texas HB 1549, 2017) mandating medical evaluation within 3 days of entering care; within thirty days, a health supervision visit; and, for children ages 3 and older, a mental health examination using the Child and Adolescent Needs and Strengths Assessment (John Praed Foundation, 2017). The Rees-Jones Center is a member of the Texas Foster Care Roundtable and leads the North Texas Region 3 Foster Care Consortium, which has representatives from child welfare, child advocacy agencies, schools, legal systems, and medical and behavioral providers.

Lessons Learned and Future Directions

In 2019, the Center conducted a reassessment of the strategic plan, with a redefined mission, “To be the trusted health resource making life better for children in foster care,” and vision, “To achieve hope, health and healing for all children in foster care.” Strategies to address challenges facing children in foster care were reassessed in the context of the current political and health care climate. The 2018 Texas Legislative Session’s focus on child welfare and the passage of the Federal Families First Prevention Services Act provided opportunities to reframe Center goals and priorities. Increased focus was placed on examining health outcomes, program evaluation, and increasing advocacy for quality health care at the regional and state level.

Guidelines for Creating an Integrated Care Model for Foster Children

Focus on Sustainability of Funding.

Many clinical positions are grant-funded or supported by the children’s health system or academic institutions. Billing and reimbursement within the context of these systems is administratively complex. It is crucial to have upfront support regarding access to billing and reimbursement information at the provider, institutional, and insurance levels. For example, review of billing PCP and BHP time revealed denied reimbursement depending on what order behavior and medical services billing occurred. Addressing this required systemic changes in the institutional billing and electronic medical record, such as enabling separate PCP and BHP encounter scheduling and education of the children’s hospital and academic institution’s billing departments. Future strategies for sustainability include advocating for increased reimbursement statewide and exploring alternate sources of funding. Since all children involved with child welfare could benefit from integrated, trauma-informed care, providing services to children who remain with their biological parents receiving child welfare services, children who have been reunified with biological families, children who have been adopted or aged out of the foster care system, and unaccompanied immigrant minors in federal foster care could increase revenue.

Coordinate Processes for Communication Across Stakeholders.

Continuous reassessment of communication among clinic providers and child welfare workers, clinic PCPs and BHPs, and with caregivers and community stakeholders is important. Standardizing communication methods based on urgency can decrease information overload and ensure the most pressing issues are addressed. For example, email can be used for issues needing an answer within a few days, instant messaging can be used for urgent questions requiring little or no discussion, and phone calls can be used for more complex problems.

Develop Community Partnerships.

Community engagement is crucial to success of an integrated care clinic. Champions from the Center’s Family Advisory Council, which includes foster and adoptive caregivers, ensure referrals of children to the clinic and provide a crucial caregiver perspective. Kinship caregivers, former foster youth, and biological parents are under-represented in discussions surrounding the care of children in foster care, and a community development coordinator can work with clinics to improve the diversity of stakeholders.

Taking a leadership role in consortiums and advocacy groups ensures that medical and behavioral health issues are always included in discussions on how to improve outcomes for children in foster care.

Invest in Education and Training.

It is important to provide opportunities for training and education of future health professionals and the wider community. Students in medical, psychology, and public health disciplines often have no exposure to foster care; a trauma-informed integrated care clinic can increase the number of professionals caring for these children. Shared mentoring and limiting the number of learners can address challenges around increased visit times and multiple learners. Providing community trainings on topics of interest can inform caregivers and child welfare workers on important topics affecting children in foster care. Clinic providers have provided trainings on caring for drug-exposed infants, managing problems behaviors, addressing sensory differences, and trauma-informed parenting. Engagement with legal professionals and community PCPs and BHPs are next steps to increase awareness of the impact of child welfare involvement on health outcomes and the importance of trauma-informed care.

Seek Out Institutional Support.

Engage leadership at your hospital, medical system, and Medicaid in the planning process. Investment in clinic space, longer visit times, financial support to cover shortfalls in revenue generation, and support staff are needed to support an integrated model. Advocacy for child welfare and health insurance reimbursement for evidence-based medical and behavioral health care should be included in development plans.

Pursue Formal Data Sharing Agreements to Facilitate Outcome Evaluation.

Attention to detail regarding planning for evaluating health outcomes needs to be a part of the initial planning process. It is crucial to understand legal and ethical issues surrounding data sharing and approval for research involving children in child welfare custody. Establishing formal agreements for information sharing with child protective services early in the planning process could improve the ability to evaluate care delivery models and health outcomes. Concerns surrounding privacy of children and families involved in child welfare limits the use of data obtained outside of a medical encounter and has constrained robust evaluation of data of children seen in the clinic.

Continuous Assessment and Quality Improvement.

Engage early in national initiatives supporting trauma-informed integrated care. The Center’s involvement in the Pediatric Integrated Care Collaborative and the National Child Traumatic Stress Network’s Trauma Informed Organizational Assessment revealed gaps in knowledge and training at the clinic and institutional level and informed the standardization of training for clinic staff in culturally sensitivity, trauma-informed care, diversity training and expansion of training on trauma informed care to the institution.

COVID-19 Impact

The current COVID-19 pandemic has presented challenges and opportunities for the Rees-Jones Center. Social distancing limited the number of in-person clinical staff and postponed non-urgent visits. Telehealth for psychiatry was already in pilot phase, but had not been implemented for primary care visits, integrated visits, or behavioral therapy. Rapid implementation of telehealth in both medical and behavioral health care enabled the delivery of therapy and many types of sick visits and follow up medical care. A one-way traffic flow, clustering sick appointments, and standardizing all visits to 60 minutes allowed minimizing exposure in clinic. Challenges with PCPs and BHPs working in multiple locations were addressed with protocols for communication and telehealth visit platforms. Integrated visits with PCPs in clinic and BHPs on virtual platforms were piloted and then fully implemented. An on-call BHP in clinic provides urgent consultation for PCPs if needed. COVID-19 updates facilitated timely information sharing regarding the rapidly evolving public health information and policy and operational updates at the clinic, institutional, county, state, and national levels. Decreased clinic volume increased available time for non-clinical projects. Workgroups updated the Center’s website, published a white paper on the impact of COVID-19 on children in foster care, created novel web-based caregiver and stakeholder trainings, and implemented trauma-informed organizational assessment findings.

Conclusions

The Rees-Jones Center for Foster Care Excellence strives to continue to work to fulfill the mission of making life better for all children in foster care. This multi-disciplinary framework can serve as a model to promote collaboration and communication with all stakeholders who are committed to helping children and their families receive needed support and improve outcomes. Shifts toward prevention and family-based interventions provide opportunities to incorporate medical and behavioral health services into a strength-based, trauma-informed, family-centered approach that will ultimately benefit children. Children in foster care need to be served by a multi-disciplinary approach that involves the collaboration of child welfare systems, schools, and the judicial/legal system. Children in foster care benefit when medical and behavioral health providers collaborate in a fully-integrated care delivery model.

Abbreviations

Primary Care (Medical) Providers (PCPs), Behavioral Health Providers (BHPs) Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs)

Author Note

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose relevant to this work. The Rees-Jones Center for Foster Care Excellence receives funding from the Rees-Jones Foundation and the Meadows Foundation.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to: Kimberly E. Stone, MD, MPH, FAAP, Rees-Jones Center for Foster Care Excellence, 7601 Preston Road, MC P2.05, Plano, Texas 75024

email: Kimberly.Stone@utsouthwestern.edu

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge Laura Lamminen, Jill Mcleigh, Anna Flores, Heidi Roman, and Hilda Loria for their support of this work, and thank all those working to improve the lives of children in foster care.

Suggested Citation: Stone, Kimberly E., Pollard, Sara & Moore, Sara, Development of an Integrated Medical and Behavioral Health Care Model for Children in Foster Care, in The Future of Foster Care: New Science on Old Problems by the Penn State Child Maltreatment Solutions Network (Sarah Font ed. & Yo Jackson ed., 2021). https://doi.org/10.26209/fostercare5

References

Ader, J., Stille, C. J., Keller, D., Miller, B. F., Barr, M. S., & Perrin, J. M. (2015). The medical home and integrated behavior health: Advancing the policy agenda. Pediatrics, 135(5),909-917. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2014-3941

American Academy of Pediatrics. (2020). Healthy Foster Care America Models of Care. https://www.aap.org/en/patient-care/foster-care/models-of-care-for-children-in-foster-care

American Academy of Pediatrics, District II Task Force on Health Care for Children in Foster Care. (2005). Fostering health: Health care for children and adolescents in foster care. American Academy of Pediatrics.

American Academy of Pediatrics. (2015). Health care issues for children and adolescents in foster care and kinship care. Pediatrics, 136(4), e1142-1166. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-2656

American Academy of Pediatrics. Trauma Toolbox. https://www.aap.org/en-us/advocacy-and-policy/aap-health-initiatives/healthy-foster-care-america/Pages/Trauma-Guide.aspx#trauma

Bartlett, J. D, Barto, B., Griffin, J. L., Fraser, J. G., Hodgdon, H. & Bodian, R. (2016). Trauma-informed care in the Massachusetts Child Trauma Project. Child Maltreatment, 21(2),101-112. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077559515615700

Bennett, C. E., Wood, J. N. & Scribano, P. V. (2020). Health care utilization for children in foster care. Academic Pediatrics, 20(3), 341-347. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2019.10.004

Berger, L. M., Cancian, M., Han, E., Noyes, J. & Rios-Salas, V. (2015). Children’s academic achievement and foster care. Pediatrics, 135(1) e109-e116. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2014-2448

Bramlett, M. D., & Radel, L. F. (2014). Adverse family experiences among children in nonparental care, 2011-2012. National Health Statistics Reports, 74, https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhsr/nhsr074.pdf

Butler M., Kane R. L., McAlpine D., Kathol, R. G., Fu S. S., Hagedorn H., & Wilt T. J. (2008). Integration of mental health/substance abuse and primary pare No. 173 (Prepared by the Minnesota Evidence-based Practice Center under Contract No. 290-02-0009.) AHRQ Publication No. 09E003. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Campbell, K.A., Wuthrich, A. & Norlin, C. (2020). We have all been working in our own little silos forever: Exploring a cross-sector response to child maltreatment. Academic Pediatrics,. 20(1),:46−54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2019.06.004

Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services. (2014). EPSDT-A guide for states: Coverage in the Medicaid benefit for children and adolescents. https://www.hhs.gov/guidance/sites/default/files/hhs-guidance-documents/epsdt_coverage_guide_112.pdf .

Center of Excellence for Integrated Health Solutions. (2017) Trauma-informed approaches: Practical strategies for integrated care settings. https://www.thenationalcouncil.org/resources/trauma-informed-approaches-practical-strategies-for-integrated-care-settings/

Child Welfare Information Gateway. (2015). Healthcare coverage for youth in foster care-and after. US Department of Health and Human Services, Children’s Bureau.

Child Welfare League of America. (2007). CWLA standards of excellence for health care services for children in out‐of‐home care. Child Welfare League of America.

Cohen, J.A., Mannarino, A.P., & Deblinger, E. (2012). Trauma-Focused CBT for Children and Adolescents: Treatment Applications. New York: Guilford.

Deutsch, S. A., & Fortin, K. (2015). Physical health problems and barriers to optimal health care among children in foster care. Current Problems in Pediatric and Adolescent Health Care, 45(10), 286–291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cppeds.2015.08.002

Dickens, M. D., Green, J. L., Kohrt, A. E., & Pearson, H. A. (1992). The medical home. Pediatrics, 90(5), 774.

Dosreis, S., Yoon, Y., Rubin, D. M., Riddle, M. A., Noll, E., & Rothbard, A. (2011). Antipsychotic treatment among youth in foster care. Pediatrics, 128(6), e1459-e1466. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2010-2970

Duffee, S., Szilagyi, M., Forkey, H., and Kelly, E.T. (2021). Pediatrics, Trauma Informed Care in Child Health Systems. 148(2). e2021052579; https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2021-052579.

Espeleta, H. C., Bakula, D. M., Sharkey, C. M., Reinink, J., Cherry, A., Lees, J., Shropshire, D., Mullins, L. L. & Gillaspy, S. R. (2020). Adapting pediatric medical homes for youth in foster care. Extension of the American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines. Clinical Pediatrics, 59(4/5), 411-420. https://doi.org/10.1177/0009922820902438

Felitti, V. J., Anda, R. F., Nordenberg, D., Williamson, D. F., Spitz, A. M., Edwards, V., Koss, M. P., & Marks, J. S. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adulthood. American Journal of Preventive Medicine,14(4), 245–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00017-8

Forkey, H., & Szilagyi, M. (2014). Foster care and healing from complex childhood trauma. Pediatric Clinics of North America, 61, 1059-1072. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcl.2014.06.015

Forkey, H., Szilagyi, M., Kelly, E. T., Duffee, J., & COUNCIL ON FOSTER CARE, ADOPTION, AND KINSHIP CARE, COUNCIL ON COMMUNITY PEDIATRICS, COUNCIL ON CHILD ABUSE AND NEGLECT, COMMITTEE ON PSYCHOSOCIAL ASPECTS OF CHILD AND FAMILY HEALTH (2021). Trauma-Informed Care. Pediatrics, 148(2), e2021052580. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2021-052580

Godoy, L., Long, M., Marschall, D., Hodgkinson, S., Bokor, B., Rhodes, H., Crompton, H., Weissman, M., & Beers, L. (2017). Behavior health integration in health care settings: Lesson learned from a pediatric hospital primary care system. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 24, 245–258. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10880-017-9509-8

Greiner, M. J., & Beal, S. J. (2018). Developing a health care system for children in foster care. Health Promotion Practice, 19(4), 621-628. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839917730045

Hagan, J.F., Shaw, J.S. & Duncan, P.M (eds). (2017) Bright Futures: Guidelines for Health Supervision of Infants, Children and Adolescents, 4th ed. Elk Grove, Village, IL, American Academy of Pediatrics

Hansen, R. L., Mawjee, F. L., Barton, K., Metcalf, M. B., & Joye, N. R. (2004). Comparing the health status of low-income children in and out of foster care. Child Welfare, 83(4), 367-380.

Horwitz, S. M., Storfer-Isser, A., Kerker, B. D., Szilagyi, M., Garner, A., O'Connor, K. G., Hoagwood, K. E., & Stein, R. E. (2015). Barriers to the Identification and Management of Psychosocial Problems: Changes From 2004 to 2013. Academic pediatrics, 15(6), 613–620. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2015.08.006

John Praed Foundation. (2017) Standard Child and Adolescents Needs and Strengths (CANS) Forms. https://praedfoundation.org/general-forms-cans/

Johnson, C., Silver, P., & Wulczyn, F. (2013). Raising the bar for health and mental health services for children in foster care: Developing a model of managed care. Council of Family and Child Caring Agencies.

Kolko, D. J., & Perrin, E. (2014). The integration of behavioral health interventions in children's health care: Services, science, and suggestions, Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 43(2), 216-228, https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2013.862804

Korsen, N., Narayanan, V., Mercincavage, L., Noda, J., Peek, C. J., Miller, B. F., Unutzer, J., Moran, G., & Christensen, K. (2013). Atlas of integrated behavioral health care quality measures. (2013). Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. AHRQ Publication No. 13-IP002-EF.

Lamminen, L. M., McLeigh, J. D., & Roman, H. K. (2020). Caring for children in child welfare systems: A trauma-informed model of integrated primary care. Practice Innovations, 5(1), 55–64. https://doi.org/10.1037/pri0000108

Levinson, D.R. (2015). Not all children in foster care who were enrolled in Medicaid received required health screenings. US Department of Health and Human Services. OEI-07-13-00460. https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-07-13-00460.pdf.

Levy, S. L., Hill, E., Mattern, K., McKay, K., Sheldrick, C., & Perrin, E. C. (2017). Colocated mental health/developmental care. Clinical Pediatrics, 56(11), 1023-1031. https://doi.org/10.1177/0009922817701172

Marsac, M. L., Kassam-Adams, N., Hildenbrand, A. K., Elizabeth Nicholls, E., Flaura K., Winston, F. K., Leff, S. S., & Fein, J. (2016). Implementing a trauma-informed approach in pediatric healthcare networks. JAMA Pediatrics, 170(1), 70-77. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.2206

McNeil, C.B. & Hembree-Kigin, T. L. (2010). Parent-Child Interaction Therapy, Second Edition. New York: Springer.

Mekonnen, R., Noonan, K., & Rubin, D. (2009). Achieving better health outcomes for children in foster care. Pediatric Clinics of North America. 56(2). 405-415. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcl.2009.01.005

Merrick, M. T., Ford, D. C., Ports, K. A., Guinn, A. S., Chen, J., Klevens, J., Metzler, M., Jones, C. M., Simon, T. R., Daniel, V. M., Ottley, P., & Mercy, J. A. (2019). Vital signs: Estimated proportion of adult health problems attributable to adverse childhood experiences and implications for prevention. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 68(44), 999-1005. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6844e1

Mufson, L., Rynn, M., Ynes-Lukin, P., Choo, T. H., Soren, K., Stewart, E., & Wall, M. (2018). Stepped care interpersonal psychotherapy treatment for depressed adolescents: A pilot study in pediatric clinics. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 45(3), 417-431. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-017-0836-8

National Council for Behavioral Health. (2020). Center for Excellence for Integrated Health Solutions. SMAHSA-HRSA Center for Health Care Solutions: https://www.thenationalcouncil.org/integrated-health-coe/resources/

National Child Traumatic Stress Network. (2018). Trauma informed integrated care for children and families in healthcare settings. https://www.nctsn.org/resources/trauma-informed-integrated-care-children-and-families-healthcare-settings.

Pediatric Integrated Care Collaborative (PICC) Toolkit. (2009). Trauma Informed Integrated Care. Johns Hopkins University. https://cmht.johnshopkins.edu/assets/ii-trauma-informed-integrated-care.pdf

Peek, C. J. (2013). Lexicon for behavioral health and primary care integration: Concepts and definitions developed by expert consensus. Agency for Health Care Research and Quality. AHRQ Publication No. AHRQ 13-IP001-EF, 2013.

Pires, S.A., Stroul, B.A., & Hendricks, T.H. (2013). Making Medicaid work for children in foster care: Examples from the field. Center for Health Care Strategies, Inc. www.chcs.org/media/Making_Medicaid_Work.pdf.

Platt, R. E., Spencer, A. E., Burkey, M. D., Vidal, C., Polk, S., Bettencourt, A. F., Jain, S., Stratton, J. & Wissow, L.S. (2018). What’s known about implementing co-located paediatric integrated care: A scoping review. International Review of Psychiatry, 30(6), 242-271. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540261.2018.1563530

Raghavan, R., & McMillen, J. C. (2008). Use of multiple psychotropic medications among adolescents aging out of foster care. Psychiatric Services, 59(9), 1052-1055. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.59.9.1052

Raghavan, R., Inoue, M., Ettner, S.I., Hamilton, B.H. & Landsverk,, J. (2010). A preliminary analysis of the receipt of mental health services consistent with national standards among children in the child welfare system. American Journal of Public Health. 100 (4). 742-749. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2008.151472

Rubin, D. M., O'Reilly, A., Luan, X., & Localio, A.R. (2007) The impact of placement stability on behavioral well-being for children in foster care. Pediatrics, 119(2), 336–344. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2006-1995

Sia, C., Tonniges, T. F., Osterhus, E. & Taba, S. (2004). History of the medical home concept. Pediatrics, 113,1473-1478.

Strathearn, L., Giannotti, M., Mills, R., Kisely, S., Naiman, J., & Abajobir, A. (2020). Long-term cognitive, psychological and health outcomes associated with child abuse and neglect. Pediatrics. 148(4). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-0438

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2014). SAMHSA’s concept of trauma and guidance for atrauma-informed approach. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 14-4884. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration. (2021). Integration Practice Assessment Tool. https://www.thenationalcouncil.org/resources/integration-practice-assessment-tool-ipat/.

Szilagyi, M. A., Rosen, D. S., Rubin, D., & Zlotnik, S. (2015). Health care issues for children and adolescents in foster care and kinship care technical report. Pediatrics, 136, e1142-e1166. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-2656

Task Force on Health Care for Children in Foster Care. (2005). Fostering Health: Health care for children and adolescents in foster care. 2nd edition. American Academy of Pediatrics.

Terrell, L., Skinner, A. & Narayan, A. (2018). Improving timeliness of medical evaluations for children entering foster care. Pediatrics.142(6), e20180725. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2018-0725

Turney, K. & Wildeman, C. (2016). Mental and physical health of children in foster care. Pediatrics, 138(5),e20161118. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-1118

Whitgob, E. E. & Loe, I. M. (2018). Impact of chronic medical conditions on academics of children in the child welfare system. Front. Public Health. 6,267. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2018.00267

Zlotnik, C., Tam, T. W., & Soman, L. A. (2012) Life course outcomes on mental and physical health: The impact of foster care on adulthood. American Journal of Public Health, 102(3), 534–540. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2011.300285

Zlotnik, S., Wilson, L., Scribano, P., Wood, J. M., & Noonan, K. (2015). Mandates for collaboration: Healthcare and child welfare policy and practice reforms create the platform for improved health for children in foster care. Current Problems in Pediatric Health Care, 45, 316-322. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cppeds.2015.08.006

This work is licensed under a

This work is licensed under a